Marco Polo travels east to the court of Kublai Khan in a Silk Road caravan during the Pax Mongolica, from the Catalan Atlas c. 1375 CE

In 2020, we completed our staged transition from the Age of Earth, to the Age of Air. These grand units of time are defined by the Jupiter-Saturn conjunctions occuring in signs of the same element, with the ruling element shifting approximately every 200 years.

Those elemental rulerships have something to say about the kind of things that play out during those eras, and the sorts of motivations, inventions and ideas that gain currency during them.

Interestingly, at either end of these 200 year blocks, we got a blending of significations as these conjunctions dance back and forth over an elemental sign boundary. From 1842, to 1979, every conjunction landed in earth signs and what did we get for our troubles? The rise of both scientific and economic matter-ialism, the industrial revolution, and huge global land wars, to name but a few.

Then in 1980, we got our first taste of a great conjunction in air signs. Electrifying, communicative, dynamic, boundaries eroded. Synths! Suddenly we’re using computers, we have mobile phones, we decide unregulated markets are somehow a good idea, the earliest iterations of the internet begin to connect US military systems around the world, neutral networks and machine learning begin to pick up speed.

The past 40 odd years have been a blend of earth and airy, with computing and informational technology predominantly harnessed towards industrial, economic and material goals. My friend Sadalsvvd explores this much better and more fully in their fantastic essay, Flowing into the Age of Air, which I’d advise you to read for a more detailed exploration of our current incoming airy epoch.

We’ve Been Here Before

One of the best things about astrology is that it is the study of cycles, and of the qualitative nature of time. So where better to look for insight into our current Age of Air, then the last time the world found itself grappling with the decentralising and connective forces of this element.

.jpg)

The cyclic pattern of Great Conjunctions, from Johannes Kepler's De Stella Nova (1606)

I was curious about how the last Age of Air showed up, and had my suspicions that it would correspond with a specific period in history that always felt very air-coded to me. The era to which I am referring is the so-called Pax Mongolica.

So what is it? Well it means Mongol Peace, and is a play on Pax Romana (Roman Peace). Roman historian Tacitus, putting words in the mouth of vanquished Celtic chieftain Calgacus, famously said of the Romans that “They make a desolation and call it peace.” And that’s not a terrible way to speak of Pax Mongolica too, or at least its foundation.

The Pax Mongolica is what remained after Ghenghis Khan – nowadays referred to as Chinggis Khan – united the tribes of the Mongolian steppe, and created the largest contiguous land empire the world has ever seen. These conquests were incredibly bad news for those on the receiving end, with an estimated 10% of the world’s population said to be killed in this wave of expansion and many great cities of the medieval Islamic world, such as Merv and Nishapur, razed to dust in their wake.

This was hugely disruptive, not just to regular people’s lives, but to the entire established world through which the Mongols rode. In Europe, men in tights with bowl cuts were charging at each other with big sticks and picking roses. In the Islamic world, the Arab conquests of the 7th century were a distant memory, and the Abbasid Caliphate ruled over a golden age of Islamic learning with Baghdad’s famous House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Ḥikma) at its heart. And Song dynasty China continued to carry the mantle of the world’s oldest continuous civilisation, with any and all preceding barbarian incursions either comfortably repelled, or intentionally integrated within their cultural sphere.

Steppe by Steppe

Connecting these disparate dots was the Silk Road, which had indeed been around for a very long time at this point, with the earliest evidence of trade between China and Europe along the land route tracing back to 130 BCE. But travel along it was hugely perilous, with large relatively lawless swathes exposing traders and pilgrims to mortal danger. It also moved through a dense patchwork for feudal kingdoms and larger empires, each with their own laws and tariffs. Most trade was over comparatively short distances, with items changing hands and moving across these many borders in little steps.

The Mongols, whose unified empire quickly splintered into a number of successor states such as the fantastically named Golden Horde, did away with these entrenched structures and rigid borders, and this has a lot to do with the environment that shaped them.

The Eurasian Steppe runs from Manchuria in Northeast China to Hungary, a distance of about 5000 miles

The Eurasian steppe is a giant, largely flat grassland that runs from the Pacific coast of North-eastern China to the inland plains of Hungary. When the horse was domesticated around 3500 BCE, the pastoral nomads of this vast ocean of grass were suddenly able to move with great speed, transforming trade, warfare and culture and leading to a unique admixture of peoples, religions and languages.

For millennia, raiding tribes from the steppe had long been a fact of life for the settled civilisations that had bordered them. What made the Mongols different was their openness to innovation and experimentation – distinctly airy qualities.

Universal Oceanic Ruler

Temüjin proclaimed Chinggis Khan with his sons, Jāmiʿ al-Tawārīkh, c. 1430.

Temüjin, born 1162, was a minor noble who rose to consolidate power against the backdrop of incessant war, raiding and clan conflict that characterised Mongol society at the time. Where he distinguished himself from other warlords was in his ability to ultimately unify the Mongol tribes under his leadership.

In 1206, he was crowned as Chinggis Khan (Universal/Oceanic Ruler), marking the beginning of his aggressive global expansion. That very same year saw the final great conjunction in earth signs for that outgoing epoch. The next conjunction, that launched the Age of Air in earnest, was in 1226 – Chinggis Khan died in 1227.

Thus we can see that his time in power maps pretty perfectly over this final earth phase, in which we’d expect to see airy innovations from the incoming cycle harnessed for earthy goals (such as land conquest).

Over the prior 20 year air period, Temüjin introduced a new legal code that standardised laws across the Mongol clans, instated a postal courier system that facilitated rapid, long distance communication, and the introduced meritocratic leadership in all levels of his administration – decentralising power and doing away with centuries of aristocratic rule-by-pedigree.

He also oversaw cutting edge reforms in his military with the introduction of new tactics and weapons – these included early gunpowder lances and siege engines, and most significantly a new composite bow that was lighter, more powerful and easier to fire from horseback. Greater ease of movement, longer ranges.

As he and his armies expanded out of Mongolia, they recruited the talented leaders, thinkers and engineers among those they defeated into their meritocratic system, in doing so they grew more sophisticated and capable with each outward step.

The end result of all of this marauding was the Pax Mongolica. Once the entrenched power structures across medieval Eurasia had been destroyed or degraded in the wake of their conquests, what was left was highly decentralised and pluralistic.

Web Zero

The Mongol successor states that arose out of Chinggis Khan’s land-grab integrated with the local cultures, religions and traditions over which they ruled while retaining key pan-Mongol innovations and conventions.

Of these, it’s hugely significant that the Yassa legal code was retained. That meant that a territory spanning from Poland to Korea had a shared enforceable set of legal conventions that included freedom of religion for all subjects, protected trade routes across its entire span, enshrined the meritocratic basis for Mongol government, and prosecuted people for any interference with the postal system.

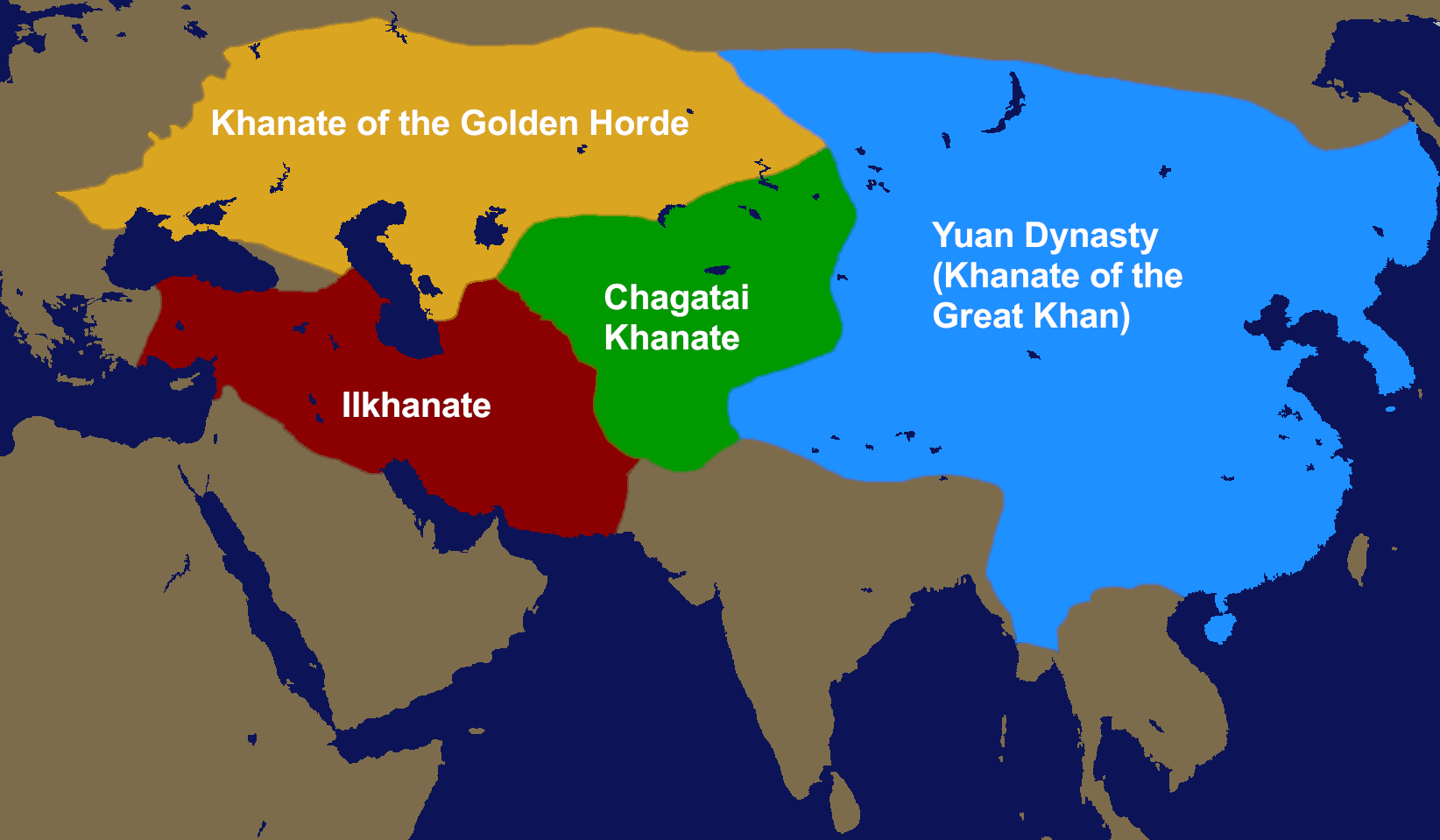

The Four Khanates of the Mongol Empire c. 1300 CE

That postal system is another crazy thing to me. Called the Yam system, this relay network was maintained across this entire region with way-stations offering fresh horses, lodgings and supplies positioned no more than 25 miles apart across the whole empire. This meant that news could travel at about 185 miles per day, which was 10x faster than was possible in feudal Europe at the time, and a similar speed to America’s 19th c. Pony Express. This made it possible, for example, for Kublai Khan in Yuan China to relay messages with Berke Khan in Europe in just a number of weeks.

The end result was that scholars from the centres of learning of the Islamic Golden Age, for the first time, could freely travel and exchange knowledge at unprecedented speed with their counterparts in dynastic China and the fringes of medieval Europe.

This is the Age of Air. Top-down power structures were highly decentralised, national borders were incredibly fuzzy concepts – I mean, where exactly is the edge of a horde? Information and news is able to move in any direction, at incredible speed, and this all gives rise to new philosophical, social and scientific ideas.

Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine reached China, and TCM pulse diagnosis entered Islamicate medicine. Algebra influenced Chinese mathematics while decimal-based calculations from China spread to Europe and the Islamic world. The works of Plato, Aristotle, Ptolemy, transmitted via Persian scholars, reached the Chinese court, as Chinese astronomical tables influenced Islamicate star charts.

.jpg)

From a manuscript of Mongolion medical astrology c. 1700

Tibetan Buddhist texts were being discussed in Tabriz, the capital of the Ilkhanate near the modern-day border of Türkiye, as Sufism became widespread in Persia. Paper money and gunpowder weapons flowed out of China, while European glass lenses and Islamic astrolabes flowed in.

Social Distancing

It bears noting though that connectivity is not selective, and things other than ideas and goods can make great use of these networks. Thus it was that the Pax Mongolica would appear to have sown the seeds of its own downfall. The bubonic plague had been periodically breaking out in parts of China for centuries before the historic event we know as the Black Death took hold. For that to emerge, it required the rapid and easy movement of people and goods that the Mongols’ trade network offered in order to make its lasting and globe-spanning impact felt.

That our own modern Age of Air was ushered in under the auspices of another plague exploiting global networks is just a Sign of the Times. But unlike before, rather than triggering collapse, the pressures of the current pandemic have thrust our world headlong into an embrace of hyperconnectivity, dematerialisation, adaptive systems and novel technologies. Covid, after all, is respiratory in nature.

Nothing exists in isolation, and there is no such thing as history – there are histories. This is one frame I’ve placed over an enormous span of time and space because I heard the echo of our moment reflected there. The Pax Mongolica was far from a golden age, nor is the coming Age of Air, the Age of Aquarius lol. What’s clear to see though, is that this period was far more decentralised, and facilitated faster and more open communications and exchange of information than what came before. Same as how the internet has done for us.

Winds of Change

With each passing day, things have the appearance of growing ever more fragmented. There is no one truth anymore, but a multiplicity. Everyone is in a different silo. But ages of air thrive on these conditions of disruptive, fluidity and connectivity. The cultural rapprochement we’ve witnessed in recent days between the real people the make up the United States and China, as thousands of TikTok users wash up on the shores of Xiaohongshu, demonstrate perfectly that the walls between those silos are negligibly thin, and we’re able to use the technologies at our disposal to puncture them, foster new connections and develop new understandings and pathways of exchange. Banning an app might just have worked in the Age of Earth, but the rules of the game have changed.

This coming Age of Air is going to be complex to navigate, that much should be abundantly clear to anyone. With the first incoming conjunction in Air in the 1980s, the rise of the cyberpunk genre served as a powerful vision and harbinger of a time to come. Now, what was once fiction is just daily life, for better or worse.

“Change is accelerating. Invention, connection, adumbration of ideas, mathematical algorithms, connectivity of people, social systems—this is all accelerating furiously and under the control of no one; not the Catholic church, the communist party, the IMF. No one is in charge of this process. This is what makes history so interesting. It’s a runaway freight train on a dark and stormy night.

This is why I’m not particularly sympathetic to conspiracy theory, because I can’t make the leap of faith that would cause you to believe that anyone could get hold of the beast enough to control it. Conspiracies—of course we have conspiracies up the kazoo, but none of them are succeeding. They’re all being swept away, compromised, astonished by new information, and endlessly agonized.” ~ Terence McKenna

Cyberpunk’s great message is that the same tools designed to overwhelm, surveil and suppress, can be hijacked, reprogrammed and turned towards chaotic, meaningful, and even beautiful ends. Nobody was banking on the Mongols to take the ideas and technology of their more powerful neighbours, recombine them, and use them with incredible effectiveness. But they saw which way the wind was blowing.

doubtshrine.uk

doubtshrine.uk